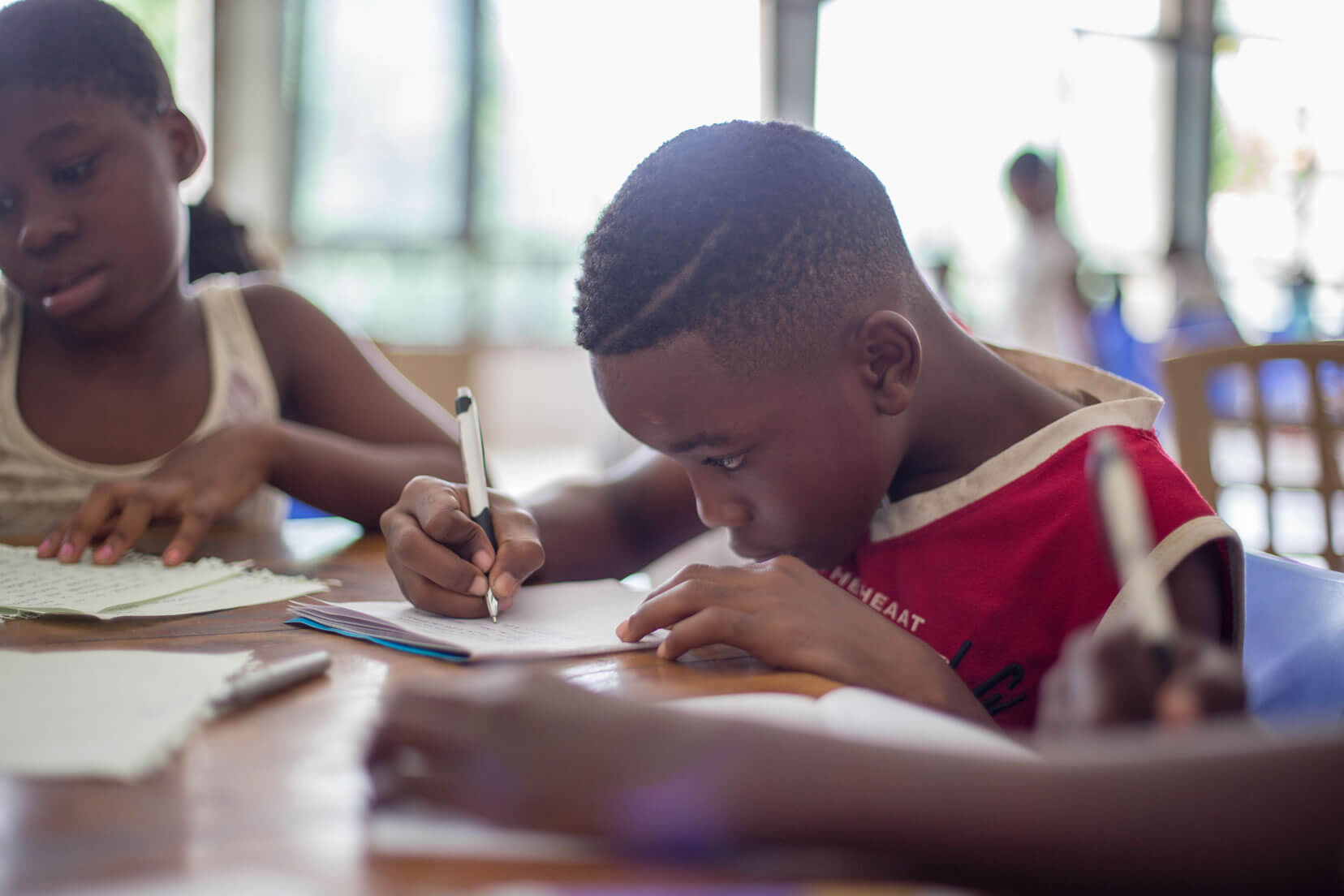

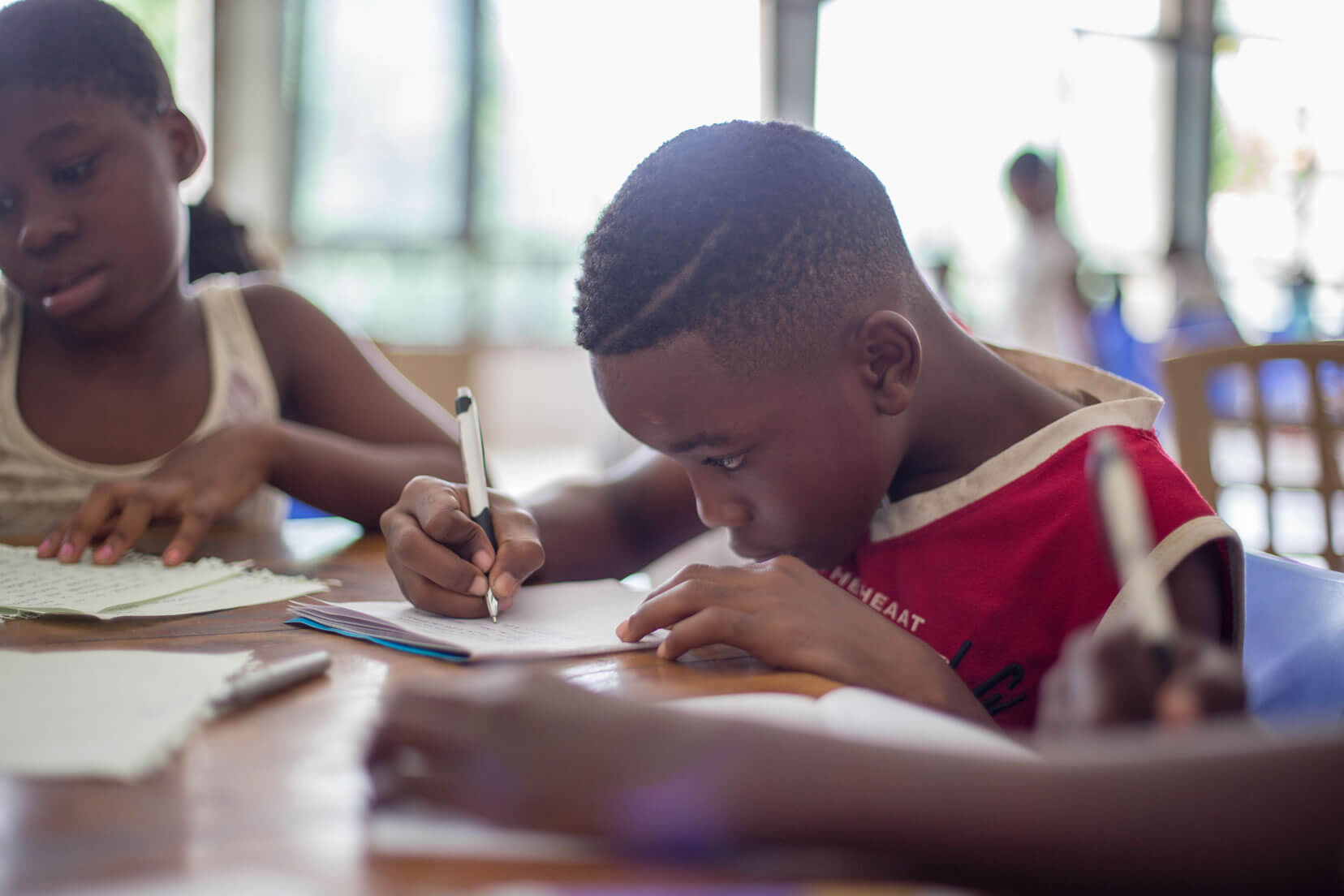

Subtle yet substantial, the burdens of educational poverty are often eclipsed by apparently more vivid indicators of health and lifestyle, access to which, are paradoxically contingent upon educational attainment. The COVID-19 pandemic poses a grave threat to multidimensional poverty as a whole, yet the palliatives of food and funds being offered by governments and NGOs attend only to the malnutrition and monetary variables, while the indicators of education are the least incentivised. That is despite the fact that 31million Nigerian children are out of school due to the pandemic, joining 13million counterparts who were never enrolled. This pattern portends severe consequences for 52% of Nigerians as adjudged by the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Trite to say, the consequences of deficits in knowledge transfer may linger into the distant future, well after the virus has departed. This paper thus explores how these consequences transcend sub) national, urban, rural, as well as gender domains. In doing so, the MPI education indicators – school attendance and a minimum of 6 years of schooling – are interrogated, bearing in mind that a problem must be identified to be solved. The interpretive method was applied to data, in the main, from the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), the Demographic Health Survey (DHS), National Social Investment Programmes (NSIP), as well as UNICEF and World Bank reports. These documents were content-analysed with perspectives from pre- and projections for post COVID-19. Deductions were drawn from 2017 to 2019, and projections made for the years 2020 onwards.

Subtle yet substantial, the burdens of educational poverty are often eclipsed by apparently more vivid indicators of health and lifestyle, access to which, are paradoxically contingent upon educational attainment. The COVID-19 pandemic poses a grave threat to multidimensional poverty as a whole, yet the palliatives of food and funds being offered by governments and NGOs attend only to the malnutrition and monetary variables, while the indicators of education are the least incentivised. That is despite the fact that 31million Nigerian children are out of school due to the pandemic, joining 13million counterparts who were never enrolled. This pattern portends severe consequences for 52% of Nigerians as adjudged by the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Trite to say, the consequences of deficits in knowledge transfer may linger into the distant future, well after the virus has departed. This paper thus explores how these consequences transcend sub) national, urban, rural, as well as gender domains. In doing so, the MPI education indicators – school attendance and a minimum of 6 years of schooling – are interrogated, bearing in mind that a problem must be identified to be solved. The interpretive method was applied to data, in the main, from the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), the Demographic Health Survey (DHS), National Social Investment Programmes (NSIP), as well as UNICEF and World Bank reports. These documents were content-analysed with perspectives from pre- and projections for post COVID-19. Deductions were drawn from 2017 to 2019, and projections made for the years 2020 onwards.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further dipped the ebbing state of school attendance, especially in northern and rural Nigeria. Given the option of online-learning, the infrastructure of which is weak, only a fraction of the 24.6% of Nigerians with daily consumption above $3.10 can sustain data requirements for a prolonged period. There are bound to be huge deficits in the school attendance drawing from the pandemic. The minimum educational attainment will also be compromised, as financial constraints worsened by the virus would force the formerly enrolled to drop out of school and drop into child-labour – hawking in the urban and farming in the rural areas. Under the force of low school attendance and educational attainment, the national literacy level is bound to nose dive. The precarious situation to arise will further erode the fundamental human right to education; thus limiting freedom and choice and enforcing a poverty trap.

Educational poverty is significantly worse off in northern Nigeria, where all the states have poverty intensity ≥0.2. Quite the opposite obtains in southern Nigeria. Indeed, OPHI reports that northern Nigeria has the highest parlous correlation between education and inequality. The Almajiri phenomenon in northern Nigeria constitutes a sour causative factor in this regard. Hence, a post-COVID-19 stimulus should target that population. Gender-wise, the educational poverty pendulum might swing from females in the pre-pandemic to males in the post-pandemic era. Global statistics point to doubly higher male fatalities from the disease. A number of remedial organs are already in place; only, their operations need to be ramped up in quality and in spread. The amount provided by CCT ought to be scaled up above the World Bank poverty limit, just as it should transform to a comprehensive Universal Basic Income in Nigeria, based on BVN or national identification. A realistic social security database ought to be harvested, which will also take into cognisance accurate figures and addresses of the beneficiaries of the School Meal Distribution Programme of the NSIP. That way, even when bound at home during pandemics, true beneficiaries could still be reached with meals.

To be armed for post-COVID-19 pandemic situations, given the limited individual resources of the citizenry, apparatus should be developed with a dedicated unit of the National Youth Service Corps to ensure the development of curriculum-based educational materials for radio and television. In the same vein, the Ministry of Agriculture should commission Agricultural Engineering Departments across the nation to fabricate low-tech mechanical tools to be mass produced and deployed to rural areas. That way, children will disengage from farms during school time. By and large, private sector participatory initiatives ought to be encouraged, alongside an above-average income pro rata tax policy, to ensure a sure stream of funding dedicated to educational poverty restraining measures.

Click the link below to read the full version.